by

Jimmy Marty

Seed identification is an important skill with applications to the agricultural and ecological sciences. In the paleolimnological community, seed macrofossils from lake sediments are identified for radiocarbon dating, environmental reconstruction, historical biogeography, and lake level fluctuations. Identifying seeds can seem a daunting task – there are ~28,000 plant taxa in North America alone – and indeed, seed identification to genus and species level requires a great deal of training, experience, and patience. This tutorial aims to provide a tool for both the beginner and expert to aid in the identification of seeds of temperate North America.

It is important to consider that although in some cases extreme and unique features can serve to distinguish one seed from another, it is much more common that several different features in combination are required in order to make a positive identification at genus and/or species level. At a very basic level, it is extremely important to take detailed notes of features of unknown specimens. In many cases, it can be helpful to draw and/or photograph them. Also indispensable is an extensive seed reference collection from the area of study. Side by side comparison is a must at fine taxonomic resolution. Reference images from books, journals, and web resources are also crucial for making comparisons with sample specimens. With these suggestions in mind, below is a list of observations one might make in order to make a positive identification of an unknown seed.

1. Specialized features

Plants have equipped their seeds with an incredibly diverse array of specialized external features for survival, dispersal and germination. These features include, but are not limited to awns (Echinocloa, Zizania),

|

| Echinochola muricata (barnyard grass) |

|

| Zizania palustris (northern wild rice) |

wings (Betula, Pinaceae)

|

| Betula papyrifera (paper birch) |

|

| Larix laricina (tamarack) |

pappus (Eupatorium),

|

| Eupatorium rugosum (snakeroot) |

bristles (Galium, Bidens),

|

| Galium triflorum (bedstraw) |

|

| Bidens cernua (nodding beggarticks) |

glumes (Poaceae),

|

| Phragmites australis (common reed) |

beak (Potamogeton),

|

| Potamogeton epihydrus (ribbonleaf pondweed) |

flesh (Prunus),

|

| Prunus serotina (black cherry) |

raphe (Violaceae),

|

| Viola pedata (mountain pansy) |

tubercle-cap (Eleocharis),

|

| Eleocharis palustris (marsh spikerush) |

and hairs (Schoenoplectus, Scirpus).

|

| Schoenoplectus acutus (hardstem bulrush) |

|

| Scirpus atrovirens (black bulrush) |

Learning to recognize these features upon sight is perhaps the most valuable skill a seed identifier can possess, but requires a fair amount of experience. Nonetheless, an inexperienced identifier can meet great success by simply noting seed features that seem unique and comparing them to reference materials. Take a look at the images associated with the features above; even if one is unfamiliar with botanical terms, they are probably able to pick out the distinguishing characteristic of each specimen. Practice recognition of these features by examining seeds in reference collections and images. Be aware that in fossil specimens, seeds may not be preserved well, especially delicate features like wings, pappus, and flesh.

2. Shape

Linear, oblong, elliptic, ovate, obovate, oval, spherical, trigonous, globose, reniform, kidney shaped, lenticular, bi-convex.

Figure 1: Outlines of some common seed shapes (http://www.grainscanada.gc.ca/guides-guides/identification/images/fig1b-e.gif).

The long list of shape descriptors provided by the botanical literature is best used as a spectrum where many hybrid shapes exist (e.g. elliptic-ovate, spherical-reniform). Description of shape may account for shape in outline and/or cross section, each of which can be useful for identification. At a family level, there are many unique shapes that help to quickly identify them, e.g.

Apiaceae,

|

| Cryptotaenia canadensis (honewort) |

Asteraceae,

|

| Eupatorium rugosum (snakeroot) |

Potamogetonaceae,

|

| Potamogeton epihydrus (ribbonleaf pondweed) |

and Polygonaceae.

|

| Polygonum scandens (false buckwheat) |

At genus and species level, seed shapes are often key to recognition due to the large diversity of shapes. Consequently, it takes a trained and experienced eye to perceive the minute differences in shape at such taxonomic level. One method for a beginner to confront this challenge is to organize seeds by shape and note differences between specimens. It is then a matter of studying reference images and specimens similar in shape until things hopefully become clear.

3. Size

Size can be useful to make both coarse and fine scale distinctions between seed types. There is a broad range of seed/fruit sizes represented in the Midwest region, from seeds best measured in microns to those measured in centimeters. In general, size can be used to direct identification. If a specimen is 1 mm long, it may be wise to invest less time examining other characteristics of families with seeds much greater (say, > 2 mm) like Nymphaceae:

|

| Nuphar lutea (yellow water lily) |

On a finer scale, specimens on the extreme edges of size range can be quickly narrowed down to just a few taxa, for example Quercus (big),

|

| Quercus macrocarpa (bur oak) |

or Juncus (small).

|

| Juncus effusus (soft rush) |

If the specimen is a less conspicuous size, size can still be useful for making distinctions between taxa within families. Slight differences in size between species can be key to positive identification. For example, Schoenoplectus acutus

|

| Schoenoplectus acutus (hardstem bulrush) |

appears very similar to Scirpus fluviatus.

|

| Scirpus fluviatus (river bulrush) |

However, Scirpus fluviatus is almost always larger.

4. Seed surface

Different surficial features are another helpful characteristic used to identify seeds on multiple taxonomic levels. Seed surface can be smooth-shiny, smooth-dull, ribbed, pitted, reticular, warty, labyrinth-patterned, dimpled, spiny, or hirsute. Certain taxa are sometimes associated with specific textures, such as the reticular seeds of Brassicaceae,

|

| Iodanthus pinnatifidus (purple rocket) |

pitted seeds of Najas,

|

| Najas flexilis (slender naiad) |

tubercle-covered Carophyllaceae,

|

| Cerastium nutans (chickweed) |

the spiral ribbing of Characeae oogonia,

|

| Chara sp. (muskgrass) |

or ribbed oil tubes of Apiaceae.

|

| Cryptotaenia canadensis (honewort) |

Slight differences in the patterns within these taxa can be used for finer scale identification. For example, carefully examining the labyrinth pattern of tubercles on the surface of Carophyllaceae reveals very minute differences that lead to species level identification. Examining the details of seed surface can sometimes be challenging, especially with small seeds or detailed patterns. SEM photographs of seed texture are one method of capturing these surfaces at high resolution, but may be overly time consuming in many cases. One simple trick is to moisten the surface of the sample specimen with distilled water, then examine the surface as the water evaporates. The moments while the seed is drying provide a clear view of the surface features.

5. Hilum

The hilum is a scar on the seed coat remaining from the attachment of the seed to the ovary wall. Some taxa have very conspicuous hilum that can immediately signal the family, such as Fabaceae on a family level and Chenopodium and Lycopus on a genus level. At a finer taxonomic level, the shape, size, and position of the hilum can help in narrowing the genera or species to be considered. For example, in Chenopodium, the hilum is indented. The indentation depth and placement on the seed is key to telling the difference between seeds (e.g. C. glaucum and C. album).

|

| Chenopodium album (goosefoot) |

|

| Chenopodium glaucum (oak-leaved goosefoot) |

See also the family Fabaceae (S. helvola), where the hilum is especially conspicuous.

6. Internal features

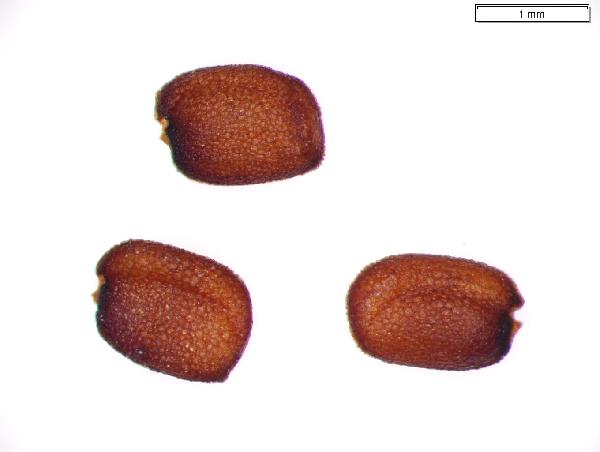

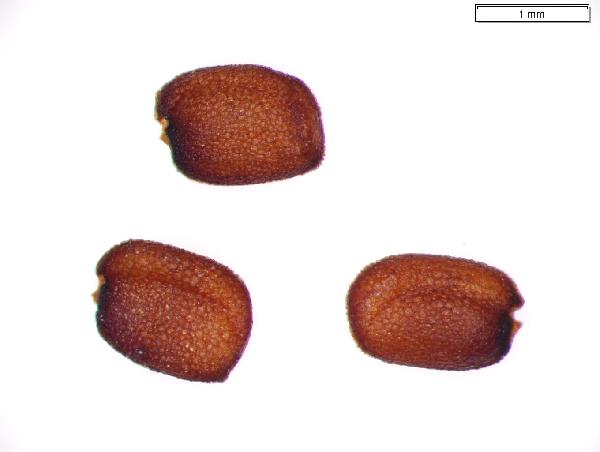

Very useful clues can be also be found on the inside of a seed by examining the shape, size and position of the embryo as well as the wall thickness and inner texture/markings. This is examination is typically done by bisecting the seed laterally with a razor blade. Some seeds may look very similar externally, but be in separate and unrelated families. A quick internal check can reveal these extreme differences (and help avoid serious mistakes). For example Morus rubra

|

| Morus rubra (red mulberry) |

bears some resemblance to some species in the genus Ranunculus,

|

| Ranunculus abortivus (buttercup) |

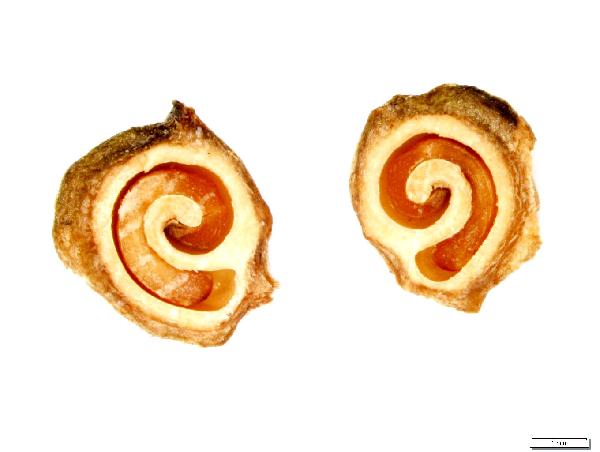

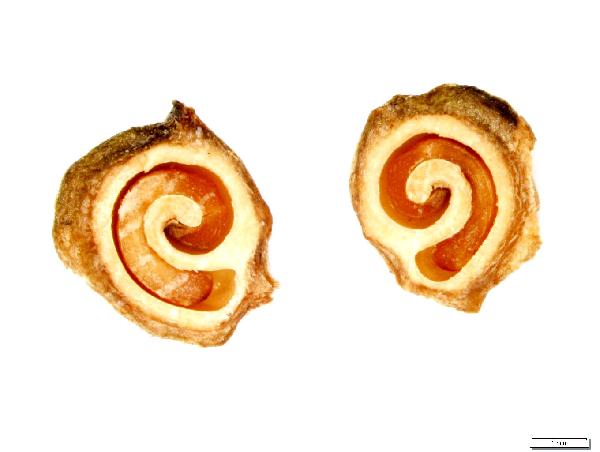

but are in different families. The inner surface of M. rubra is marked with cellular reticulations that are not present in the Ranunculus genus. Internal morphology can also assist identifications down to a species level. For instance, the most effective method of identifying Potamogeton species is comparison of the spiral shaped embryos. Note the more compressed embryo shape of P. epihydrus

|

| Potamogeton epihydrus (ribbonleaf pondweed) |

compared to P. natans.

|

| Potamogeton natans (floating leaf pondweed) |

7. Color

Color is most useful for making general observations about a seed and generally should not be used diagnostically. Color is subject to much genetic and environmental variability, particularly in fossil specimens that over time begin to appear faded. Examine the color difference between reference specimens collected in 1938 from the same Najas marina plant.

|

| Najas marina (alkaline naiad) |

While seeds can be described as “light” or “dark”, “reddish” or “yellowish”, it is most useful to use these descriptions as guidance for comparison with similarly colored reference images and samples rather than to draw any conclusions.

8. Caveats

It is important to consider that both genetic and environmental factors can dramatically effect the morphology of a seed. All of the above features are subject to variation intraspecifically and within an individual plant. Genetic variation can affect the seed in a variety of ways depending on the taxa. For example, hybridization of Potamogeton species may alter embryo shape, making identification to species level difficult to impossible. Environmental factors such as malnutrition or premature dispersal can lead to stunted development and immature seeds.

|

| Betula papyrifera (paper birch) |

|

| Eleocharis acicularis (least spikerush) |